Japan's military rise to counter China (can the Indo Pacific still rely on the US?)

Japan’s military rise is now one of the defining security stories in the Indo-Pacific. Tokyo has moved from a posture built around homeland defence and US support to one that aims to deter China directly, including the ability to strike back at launch sites and C2 infrastructure. Simply put: China’s growing maritime and missile power, repeated coercion around disputed areas, and a shared regional fear that crisis timelines are shortening.

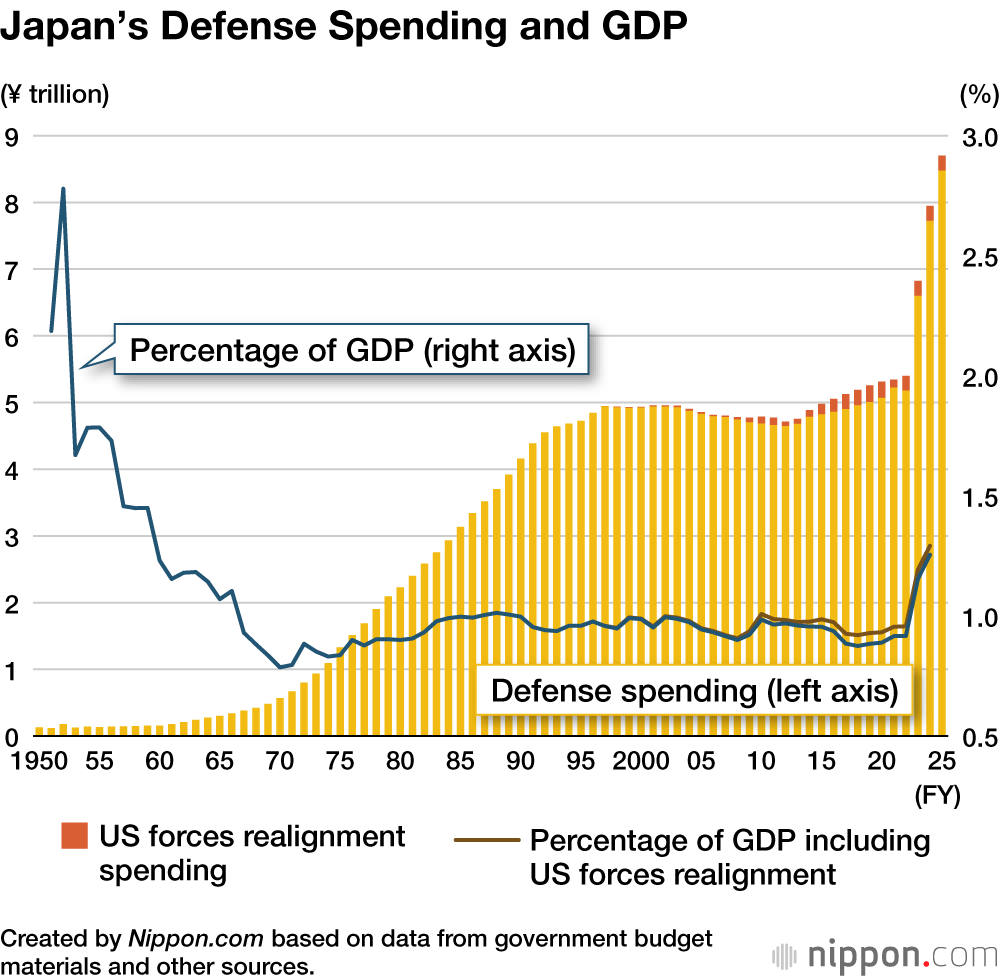

The clearest indicator is money and what it is buying. Japan is tracking toward the long-debated 2 percent of GDP defence target by 2027, backed by a multi-year buildup plan, and recent budget papers emphasise stand-off missiles, drones, and reinforced defences in the south-western island chain. This is important because it moves Japan from “deny and endure” toward “deny and punish”, creating more credible costs for any coercive move against Japan or Taiwan.

On capabilities, Japan’s emerging counterstrike package is a key talking point. Reporting indicates acceleration of the upgraded Type-12 missile deployment, with a roughly 1,000 km class range, and progress toward making destroyers Tomahawk-capable, alongside broader investment in ISR, air and missile defence, and dispersed basing. The strategic logic is to raise the cost of Chinese missile salvos and complicate Beijing’s planning by adding additional launch platforms and firing options across the first island chain.

Japan is also building out wider coalition partnerships rather than relying on a single alliance. Defence ties with Australia are deepening through formal coordination, industrial cooperation, and major naval procurement decisions that lock in interoperability for years. Partnerships with the UK and Italy through the Global Combat Air Programme show us Japan is ready to broaden high-end technology procurement beyond the US system, while still keeping the US alliance as the central pillar.

So can the Indo-Pacific still rely on the United States? The short answer is yes for hard deterrence today, but the region is hedging against future US political unpredictability. A growing body of allied commentary points to uncertainty from Washington’s tariff use and shifting prioritisation, which can create friction even when the military relationship stays strong. The US–Japan alliance remains deeply integrated across forward presence, missile defence, and increasingly defence production, and both sides still treat it as foundational for regional deterrence.

The risk is less about the US “leaving” and more about conditionality, distraction, and credibility under stress. The Pentagon review of AUKUS under an “America First” lens, and associated public debate, reinforced a wider regional perception that big defence commitments can become politically contested in Washington. That pushes partners to invest in their own strike, resilience, and sustainment so they are not waiting on a US decision in the first 72 hours of a crisis. Japan’s force design, including dispersal, stockpiles, and long-range fires, fits that pattern.

China’s likely response is to keep testing emerging vulnerabilities rather than forcing a kinetic confrontation. It's likely we will see continued grey-zone pressure around the Senkakus, increased air and maritime activity near the south-west islands, and more attempts to portray Japan as remilitarising to split ASEAN and South Korea from closer security cooperation. Regional analysis already suggests that Japan’s hard power will have mixed reception in Southeast Asia, where many governments want more balanced approaches.

Outlook for 2026: Japan’s defence rise is almost certain to continue, with missiles, drones, and south-west force posture the fastest-moving capabilities. A US security role in the Indo-Pacific remains very likely, but allies will keep building “US plus” options to cover political risk and surge requirements. A major China–Japan crisis remains possible, driven by an incident at sea or in the air, while deliberate escalation to open conflict is unlikely in the near term, assuming crisis management channels keep functioning and both sides keep prioritising control over reputation.

Responses